In Acts 5, we read that Peter and the Apostles have been brought before the Sanhedrin, whose high priest chastises them for preaching in the name of Jesus, which they had been forbidden to do. Peter and the other Apostles respond that “We must obey God, not men” (v. 29). The Sanhedrin, furious, want to put the Apostles to death. At that point, Gamaliel intervenes, pointing out that, if the apostles enjoy divine favor, the Sanhedrin would be wise to restrain themselves from any action against the Apostles. If, however, the preaching and plans of the Apostles are merely human, their efforts will soon dissolve and disappear.

In this context, Gamaliel refers to Theudas. In Biblical scholarship, there are questions about the identity of Theudas and the dates of his failed insurrection against the Romans. The point of Gamaliel’s peroration, though, is plain: Theudas was an impostor, a false messiah, a failed leader. After Theudas was killed, Gamaliel says, his followers scattered and his movement died out. Theudas’s plans were of little consequence—and that was true, said Gamaliel, about others (v. 37), also, whose ideological and military schemes amounted to nothing. That would be the possible fate, as well, of the followers of Jesus, if they were not teaching God’s truth. The Apostles were flogged but went forth joyfully to teach about Jesus the Messiah (vv. 40-42).

“Theudas,” though, has much to teach the student of politics. Chief among his legacies is the lesson that a political scheme that is disconnected from Truth will wither and die. As St. Pope John Paul put it in Centesimus Annus: “If there is no ultimate truth to guide and direct political activity, then ideas and convictions can easily be manipulated for reasons of power. As history demonstrates, a democracy without values [virtues] easily turns into open or thinly disguised totalitarianism. Nor does the Church close her eyes to the danger of fanaticism or fundamentalism among those who, in the name of an ideology which purports to be scientific or religious, claim the right to impose on others their own concept of what is true and good” (#46).

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

Theudas and his minions throughout history had no truth, so they substituted ideology, promising paradise but delivering hell. In their dystopian worlds, what mattered was the love of power, not the power of love. All their followers had to do, they said, was trust them—and the führer, or the duce, or the vozhd, or the great helmsman would soon deliver their perverted scheme of social justice. Again Pope St. John Paul: “When people think they possess the secret of a perfect social organization which makes evil impossible, they also think that they can use any means, including violence and deceit, in order to bring that organization into being. Politics then becomes a ‘secular religion’ which operates under the illusion of creating paradise in this world. But no political society—which possesses its own autonomy and laws—can ever be confused with the Kingdom of God” (Centesimus Annus, #25).

II.

Theudas is thus a type: whether of the extreme left or the extreme right, the many Theudases in history are mountebanks, political charlatans who deny God, narcissistically worship power, demand changes in religious convictions, and seek to re-build the Tower of Babel with resulting scores of concentration camps and graveyards. Still, there are the fawning, cheering crowds caught up in the fantasy that the “Great Leader” will give them, if not exactly eternal life, then meaning and joy in the years they have.

But human enterprise, alone, comes to nothing. A modern translation of Psalm 127:1 puts it this way: “If the Lord does not build the house, the work of the builders is useless; if the Lord does not protect the city, it does no good for the sentries to stand guard.” Without God, we build, not just sand castles, but quicksand castles, for the revolution, in time, will eat its own children. The renowned French statesman Talleyrand (1754–1838), asked to give the essence of politics, observed: “Surtout, pas trop de zele”—“Above all, not too much zeal.” We must not enthusiastically ask of politics what it can never provide: perfect justice and perfect mercy.

“The Church, to which Christ the Lord has entrusted the deposit of faith so that with the assistance of the Holy Spirit it might protect the revealed truth reverently, examine it more closely, and proclaim and expound it faithfully, has the duty and innate right, independent of any human power whatsoever, to preach the gospel to all peoples, also using the means of social communication proper to it” (Can. 747 §1). The Church, though, has too often blown an uncertain trumpet (1 Cor. 14:8), timid in its resolve to remind the State that its goals and its power must always be limited—and must always be consistent with the natural moral law (Gaudium et Spes, #74).

St. Paul may have said it best: “Our citizenship is in Heaven, and from it we await our savior, the Lord Jesus Christ” (Phil. 3:20). The Redeemer is from Heaven, and not from politics.

This can be distilled into five principles that ought to be integral to every political science course offered by Catholic colleges:

- “There is no permanent city for us here on earth; we are looking for the city which is to come” (Heb. 9:10). Politics is always about practical arrangements, not about redemption.

- Nolite confidere in principibus (Ps. 118:9, 147:3; CCC #407). Never trust any leader completely. Lord Acton (1834–1902) offers the corollary: “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

- Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? ∼ Juvenal (about 60-130 A.D.) Who guards the guardians? Countries require institutions such as separation of powers, checks and balances, federalism, or established traditions of limited executives to prevent consolidation of power. (See, e.g., James Madison, Federalist #51.) The danger is that, over time, such institutions may erode or be violently overthrown, resulting in aggrandized personal power and political tyranny.

- “Political authority … must be exercised within the limits of the moral order and directed toward the common good … according to the juridical order legitimately established” (Gaudium et Spes, #74). When a society loses its sense of moral order, a corrupt political system will inevitably emerge. Politics, as Russell Kirk (1918–1994) tried to teach us, is “the application of ethics to the concerns of the commonwealth.” Since Machiavelli, however, we have invariably divorced ethics and politics (different academic departments, after all)—even (or especially) in teaching political science.

- As the Manhattan Declaration (q.v.) puts it: “We will fully and ungrudgingly render to Caesar what is Caesar’s. But under no circumstances will we render to Caesar what is God’s” (Nov. 20, 2009). Separation of Church and State must never be understood to mean that the Church may not address moral failure in and by the political order.

Separation of Church and State is a commendable and practicable principle, for we have both sacred and secular duties, as Our Lord told us (Matt. 22:21). But when candidate John F. Kennedy said in Houston in 1960, “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute,” he revealed an ignorance of, and a politically expedient contempt for, the Gospel truth that we must never put Christ (Matt. 22:37) beneath lust for worldly success (cf. Exod. 20:3, Deut. 4:39-40). This was the same man who said, “I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me.” But it wasn’t, after all, his Church; it was and is Christ’s Church. Did Kennedy’s religious formation include that truth? Does ours? Are we not commanded to speak the truth in love as Christ’s witnesses (see Eph. 4:15)? Was Kennedy not baptized and confirmed, helping us to “confess the name of Christ boldly, and never to be ashamed of the Cross” (CCC #1303)—even at the price of lost votes or of diminished political power? Who does speak—boldly—for the Church? Evidently, few Catholic politicians answer that call (cf. Rev. 21:8). We owe the State loyalty—but only up to a point (see Rom. 13:7).

We are, then, as St. Thomas More said, the good servants of the king (or state), but God’s first. Our duty to the State never takes priority over our duties to God, much as St. Peter and the Apostles told the Sanhedrin. Had Kennedy ever read Acts 5?

III.

The great Swedish diplomat, Axel Oxenstiera (1583–1654), asked to give his view about political life, replied, “Quantula sapientia regitur mundus” (“With what little wisdom is the world governed”). From Saul (1 Sam. 15:10) to Herod (Matt. 2:16), the Bible is filled with accounts of stupid, incompetent, and evil rulers—with few exceptions. One of the exceptions is Josiah (2 Kings 22:2, 3:24-25) who tolerated no “disgusting idols” (23:13 GNB). This mordant translation teaches us that when we substitute anyone or anything for God we create “disgusting idols,” which may well be political.

No one has said this better than Pope Pius XI in Mit Brennender Sorge: “Whoever exalts race, or the people, or the State, or a particular form of State, or the depositories of power, or any other fundamental value of the human community—however necessary and honorable be their function in worldly things—whoever raises these notions above their standard value and divinizes them to an idolatrous level, distorts and perverts an order of the world planned and created by God; he is far from the true faith in God and from the concept of life which that faith upholds” (#8).

I find this Gospel passage chilling: “Pilate said to them, ‘Shall I crucify your King?’ The chief priests answered. ‘We have no king but Caesar’” (John 19:15). Speaking to the 2015 Women in the World Summit, Hillary Clinton declared that, “deep-seated cultural codes, religious beliefs and structural biases have to be changed.” Were we to have no queen but Hillary? The followers of Theudas disappeared after his full and final defeat. Ms. Clinton’s followers, evidently, seek a newer Theudas, a 2018 false prophet, promising a secular paradise, and muddling the sacred and profane (cf. Isa. 5:20). The political lives of new Theudases are spent in the service of disgusting idols as they defend abortion, same-sex “marriage,” euthanasia, and allied evils.

Far too many autonomous Catholics see and serve no divine law. As Pope Leo XIII taught in Sapientiae Christianae: “If the laws of the State are manifestly at variance with the divine law…, then to resist becomes a positive duty, to obey, a crime” (#10). Like Theudas, contemporary “Catholics-in-name-only” serve political causes which are often “manifestly at variance” with divine and natural law. But who will tell them?

We—including some with mitres—ignore them; or we applaud them; or we award them honorary degrees or commendations (perhaps the “Theudas Medal of Distinguished Public Service”?) at our Catholic colleges; and we elect them—and never do we excommunicate them.

Pope Leo XIII was clear that “Nothing emboldens the wicked so greatly as the lack of courage on the part of the good” (Sapientiae Christianae, #14). He did not see that, in time, legions of Catholics in political life would, in effect, sell their very souls, offering, not a pinch of incense to the secular gods, but full thuribles of it, lest they be thought insufficiently progressive and modern.

If and when we look to political power for ultimate answers to man’s most pressing and perplexing questions, we commit the sin of superstition, which is, in its full sense, the enduring danger (and the pity and the madness) of politics. May we learn the wisdom of St. Pope Pius X, who taught in E Supremi that “You see, then, Venerable Brethren, the duty that has been imposed alike upon Us and upon you of bringing back to the discipline of the Church human society, now estranged from the wisdom of Christ; the Church will then subject it to Christ, and Christ to God” (#9).

In an age of moral relativism, we too often stand uncomprehending and mute about Jacques Maritain’s apothegm that “Man is not for the State; the State is for Man.” Without moral virtue (see Prov. 14:34, 9:18, 8:15), political chaos results. And which public schools—or, for that matter, which Catholic colleges—now routinely teach moral virtue? What, after all, is truth (cf. John 18:38), and, if no one in public life dares to speak for Christ and his Church, what is the connection, if any, of truth to politics?

Theudas may be long dead, but false messiahs abound. The Church must seek, wisely and well, to influence public policy on the basis of moral principle, not assumed political power (cf. Gaudium et Spes, #42). Our responsibilities as Catholics and as citizens coincide in this regard: As Archbishop Charles Chaput put it in August 2014: “As in every other age, we’re called to preach Jesus Christ to our fellow citizens. We need to learn for ourselves and be ready to teach others the truth about the human person, the objective foundation of morality in the natural law. We need to fight to keep our human laws obedient to that deeper law. And we need to remind people of the truths they’ve forgotten, the truths on which our society is founded.”

With a certain fear, given the temptations and tendencies of modern politics, one recalls the sobering admonition of the French philosopher Etienne Gilson (1884–1978): “There still remains only God to protect Man against Man. Either we will serve Him in spirit and truth or we shall enslave ourselves ceaselessly, more and more, to the monstrous idol which we have made with our own hands to our own image and likeness.”

Theudas is dead; his apostasy—his moral and political fraud—thrives. To repeat Archbishop Chaput, whom I quoted above: “we need to remind people of the truths they’ve forgotten, the truths on which our society is founded.” That “repetition” must be bold; it must be uncompromising; it must be frequent; and it must be now.

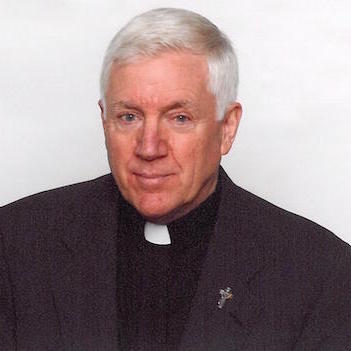

Editor’s note: Pictured above is “Give us Barabbas!” originally illustrated by Charles-Louis Muller for La Revolution 1789-1882 by Charles D’Hericault (1883).