When Luigi Calabria, a shoemaker married to a housemaid, died in Verona, Italy in 1882, the youngest of his seven sons, Giovanni, nine years old, had to quit school and take a job as an apprentice. A local parish priest, Don Pietro Scapini, privately tutored him for the minor seminary, from which he took a leave to serve two years in the army. During that time, he established a remarkable reputation for edifying his fellow soldiers and converting some of them. Even before ordination, he established a charitable institution for the care of poor sick people and, as a parish priest, in 1907 he founded the Poor Servants of Divine Providence. The society grew, receiving diocesan approval in 1932. The women’s branch he started in 1910 would become a refuge for Jewish women during the Second World War. To his own surprise, since he was a rather private person, his order spread from Italy to Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, India, Kenya, Romania, and the Philippines.

With remarkable economy of time, he was a keen reader, and in 1947 he came across a book translated as Le lettere di Berlicche by a professor at the University of Milan, Alberto Castelli, who later became a titular archbishop as Vice President of the Pontifical Council of the Laity. Berlicche was Screwtape and “Malacode” served for Wormwood. The original, of course, had been published in 1943 as The Screwtape Letters and Calabria was so taken with it that he sent a letter of appreciation to the author in England. Lacking English, he wrote it in the Latin with which he had become proficient since his juvenile tutorials with Don Pietro.

It is annoying how some assume and assert that C.S. Lewis responded in Lingua Latina only because he had no Italian. As a teenager in Northern Ireland, Lewis had become enamored of Dante, beginning with the Purgatorio and that began his fascination with Italian, including Petrarch, having first learned French and Latin, soon to embark upon Greek and other tongues including his beloved Old Norse. He quotes Italian lines from the Paradisio in his Letters to Malcolm. As a youth studying a Latin atlas of Italy, he was attracted to the name of an Umbrian town called Narnia, and put it in his memory bank where years later it bore fruit. Father Calabria knew that Latin would be second nature to an Oxford don. The sermon at the opening of each academic term is preached in Latin in the University Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, with its charming if incongruous Solomonic pillars.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

Even the Book of Common Prayer had been translated twice into Latin in the seventeenth century for university use as Liber Precum Publicarum. In the United States in 2008, an Episcopal clergyman admirably translated the updated 1979 Prayer Book into Latin, but its sales apparently were sparse because of his denomination’s demographic and theological decline, while an Hungarian’s translation of Milne’s classic as Winnie Ille Pu for precocious children, became the only Latin book ever on a New York Times bestseller list. In 1897, Saepius officio, the Latin response of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York to the Apostolic Letter of Leo XIII, Apostolicae curae, which declared Anglican orders invalid, may have been tenuous in argument, but it was widely considered to have been written in a style superior to that of the Pontiff’s. Archbishop Temple was the product of Balliol in Oxford and Archbishop Maclagan had been at Peterhouse in Cambridge where Lewis eventually became professor of Mediaeval and Renaissance Literature, juggling Latin and Italian.

Lewis was a member of the “Inklings” circle along with Dorothy Sayers. She considered her translation of the Divine Comedy her best work, while also writing an amusing essay, “The Greatest Single Defect of My Own Latin Education” about her father introducing her to involutions of the classic hexameter at the age of six. She thought eleven was an age too old to really get into it. There is a brilliant section in which she tears apart the reconstructed classical, or “Protestant,” pronunciation of Latin that Lewis spoke. There is also an eloquent and insightful book by Father Milton Walsh, Second Friends, about the acquaintance of Lewis with Monsignor Ronald Knox. While any Latinist compared to Knox would be an epigone, Lewis clearly respected Knox, even though he cultivated Tolkien much more despite the fact that, as Lewis put it, he was reared to be suspicious of papists and philologists and Tolkien was both.

Lewis’s correspondence with Calabria went on for about seven years, and after the holy priest died, Lewis wrote at least seven letters to another member of Calabria’s religious community, Don Luigi Castelli, who died in 1986 at the age of 96. Learning of Calabria’s death, Lewis referred to him in a message to Castelli with what I suspect was a deliberate invocation of the phrase about “the dearly departed” that Horace used to console Virgil on the death of Quintilius Varo: tam carum caput. It appears as well in Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley Novels. It was an unfortunate habit of Lewis to throw out letters he received when he thought he might otherwise betray confidences. So what we have are only what he sent. The letters are a radiant model of philia friendship that he described in his 1958 radio talks:

In friendship … we think we have chosen our peers. In reality a few years’ difference in the dates of our births, a few more miles between certain houses, the choice of one university instead of another … the accident of a topic being raised or not raised at a first meeting—any of these chances might have kept us apart. But, for a Christian, there are, strictly speaking no chances. A secret master of ceremonies has been at work. Christ, who said to the disciples, “Ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you,” can truly say to every group of Christian friends, “Ye have not chosen one another but I have chosen you for one another.” The friendship is not a reward for our discriminating and good taste in finding one another out. It is the instrument by which God reveals to each of us the beauties of others.

Lewis, himself an Irishman, measured Europe’s slothful indifference to the Gospel, and anticipated what is now Ireland’s more bitter adolescent rebellion against it, in his day when Ireland’s present decay was then unthinkable. A year before Calabria died, he received lines from his Oxford friend: “Ergo plerique homines nostri temporis amiserunt non modo lumen supernaturale, sed etiam lumen illud naturale quod pagani habuerunt — Therefore many men of our time have lost not only the supernatural light, but also the natural light which the pagans possessed” (Letter 26: Sept. 15, 1953). Earlier that same year he had written in much the same vein, and it is clear that he was thinking out a theory that became a core of his inaugural address “De Discriptione Temporum” in Cambridge on Nov. 29, 1954: “Nunc enim non erubescunt de adulterio, proditione, perjurio, furto, certisque flagitiis quae non dico Christianos doctores, sed ipsi pagani et barbari reprobaverunt — For now they do not blush at adultery, treachery, perjury, theft and other crimes, which I will not say Christian doctors, but the pagans and barbarians have themselves denounced” (Letter 23: March, 1953). The hostile reaction of many to his Cambridge address was only more muted and sophisticated than the angry condemnation of Solzhenitsyn’s commencement address in 1978 in the newer Cambridge. In vindication of these men’s warnings, it is a fact than such remarks would not be tolerated today even in many universities that indulge a delusional claim still to be Catholic.

In his Confessions, St. Augustine is a bit embarrassed about the sensitivity of his boyhood when he wept at Virgil’s description of the sorrows of Dido, but the polyphonic character of his writing is directly out of the Aeneid, just as the speeches of Lincoln have the cadences of the King James Bible and Shakespeare of whom he could quote reams. The rhythmic correspondence of the Oxford don and the priest of Verona reminds us, among other things, of the collapse of letter writing as a litmus of culture. For many now, the only mail is e-mail. Text messaging deletes rumination, and blocks any inner Cicero.

Assembling the thoughts above has been a little exercise in nostalgia for this writer. I knew neither of the pen pals but I can say I knew them sort of collaterally. I did know close friends and students of Lewis, including the kindly bishop, Crispian Hollis, with whom I lived for a while and assisted; his father’s biography of Thomas More was translated into Italian by Calabria’s friend Don Luigi Pedrollo. Then there was Tolkien’s eldest son, John, a priest and a most amiable man with many stories of his own. A mentor to me was Elizabeth Anscombe whose famous debate with Lewis on miracles has been misrepresented: they esteemed and helped each other a lot. The Modernist theologian, Dennis Nineham, sparred unsuccessfully with Lewis and expressed to me great irritation that Lewis had become so popular among the young. His discomfort with Lewis was not rare among the local dons who enlivened the line that “a prophet is not without honour except in his own town…” If anyone surpassed Lewis in some ways of contemplation, it was the amiable Austin Farrer to whom Lewis dedicated his Reflections on the Psalms and who ministered at his deathbed. There were others, or as Latin letter writers would say in a generally accessible way, “et cetera.”

Lewis wrote about miracles. Calabria worked them. One miracle was officially recognized in 1986 and another in 1997. On April 18, 1999, “For the honour of the Blessed Trinity, the exaltation of the Catholic faith and the increase of the Christian life, by the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, and our own, after due deliberation and frequent prayer for divine assistance, and having sought the counsel of many of our brother Bishops…” Pope John Paul II declared and defined Giovanni Calabria a saint.

Having married rather late in life, Lewis mourned his wife of a few years. He got an emotive book out of his grief, which one who was never a widower may be forgiven for thinking a bit overwrought. But Don Luigi was more indulgent and offered patient consolation after Lewis wrote in 1961 that he was journeying in solitude through this valley of tears.

In an essay in The Weight of Glory, Lewis comments: “…the worldlings are so monotonously alike compared with the almost fantastic variety of the saints.” The grave of C.S. Lewis in the Holy Trinity churchyard in Headington, Oxford, is very like the quiet place that moved Gray to write his elegy. It is very unlike the tomb of Saint Giovanni Calabria’s repose in a baroque land. There is no formal decree about the last state of the professor’s soul, but one may entertain an informal assumption that letters once passed between him and the saint in hac lacrimarum valle were not the end of the correspondence.

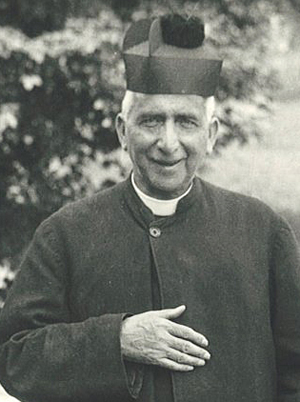

(Photo credit: C.S. Lewis / National Portrait Gallery)