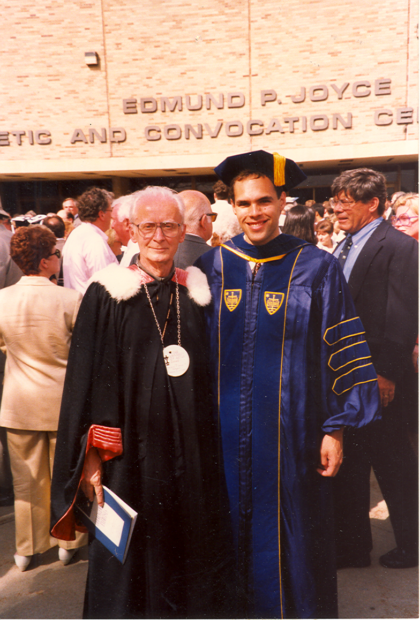

My office holds many treasured keepsakes—a wedding photo, my children’s baptismal candles, and a fiftieth anniversary picture of my parents. In sight of where I write is also a picture of a young man and an old man, a joyful 26-year-old wearing doctoral robes for the first time and a man of about 70 clad in the distinctive Laval fur trimmed doctoral regalia looking drawn and ashen. A few weeks before Ralph McInerny had triple bypass surgery, but he made the extra effort to attend the graduation in order to hood his future successor at Notre Dame as Director of the Maritain Center John O’Callaghan and myself. I keep this picture in full view to remind me of the kind of person I aspire to be, to remind me of what a full life can be.

After Ralph died, on January 29, 2010, a written memorial of the fullness of his life arose in a volume called O Rare Ralph McInerny: Stories and Reflections about a Legendary Notre Dame Professor. Ralph’s students, friends, and colleagues offered their short reflections on what Ralph meant to them and how he had touched their lives. What struck me most in putting the volume together was the integrity of Ralph’s life. The man I knew was the same man described by his brother, by the friends of his youth, and by his academic colleagues.

After Ralph died, on January 29, 2010, a written memorial of the fullness of his life arose in a volume called O Rare Ralph McInerny: Stories and Reflections about a Legendary Notre Dame Professor. Ralph’s students, friends, and colleagues offered their short reflections on what Ralph meant to them and how he had touched their lives. What struck me most in putting the volume together was the integrity of Ralph’s life. The man I knew was the same man described by his brother, by the friends of his youth, and by his academic colleagues.

Each person’s reflections highlighted a different aspect of the man, but the unity of Ralph’s life is evident in every recollection. Notre Dame Law Professor Gerry Bradley offers this gem:

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

Ralph recalled that twenty years before he had observed, right there by the Rockne Gym, several students running around “without their clothes on.” I asked if he meant that he saw some “streakers.” “Yes, yes. That was it.” I knew that the first female students were admitted to Notre Dame at just about that time. So, I inquired: “Ralph, these students you saw, were they boy streakers, or were they girl streakers?” Ralph replied calmly, “I don’t know. They all had bags over their heads.”

In addition to humor, generosity marked his life. He and Connie welcomed seven children into their lives and raised a wonderful family. He became Doktorvater to a great many more intellectual children, including Thomas Hibbs the Dean of the Honors College at Baylor, Thomas Cavanaugh the Chair of Philosophy at the University of San Francisco, and Michael Waddell the Edna and George McMahon Aquinas Chair in Philosophy at St. Mary’s College, Notre Dame. He directed 47 doctoral dissertations between 1963 and 2009, supervising theses on Hegel, Newman, Carthusian Prayer, Hume, Ortega y Gasset, Nietzsche, Pascal, Kierkegaard, Kant, Islamic philosophy, Blondel, Marcel, and of course Aristotle and Aquinas.

He was a man of who in his person combined traits rarely found in unison. As John Haldane noted:

It has often been said of analytical philosophers that they focus on arguments and conceptual distinctions for their own sake without regard to historical and cultural context or existential significance. Of Continental philosophers it has been observed that they favor poetic imagination and political disposition over analysis and reasoning. Historians of philosophy are still accused of preferring to know who said what and when, rather than to evaluate the quality of the ideas or the arguments for and against them. By education, intelligence and sensibility Ralph McInerny transcended these party distinctions and managed to engage in serious philosophical argumentation, conscious of the prejudices of past and present, and directed towards the goal of determining the nature of human beings and the ends of human thought and action.

Like his philosophical work, his own person combined strengths rarely found together. He was both unflappably calm and brewing with energy, a contemplative daily communicant and a communicator with both depth and clarity, a wit who was at the same time profound. He was at once incredibly active, yet never rushed. Despite all the endeavors as founding and being the first President of the International Catholic University, President of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars, founder of Crisis magazine and Catholic Dossier, he spent his afternoons with the door of his office open, talking with students. He must have had much to do, but he never gave us a sense of being in a hurry, or the sense that we were impinging on him.

He served these young scholars in ways good dissertation directors serve, by reading their work and by helping them get jobs. He did not insist implicitly or explicitly, as do many directors, that his students adopt his views. He did not tarry in reading and getting back to Ph.D. candidates about their work, nor did he hesitate to send something back for reworking, “I think you can do better.” He did not exacerbate but rather eased the vulnerability of that most vulnerable of campus creatures, the graduate student. He used his years of experience to gently guide graduate students around professors who would sabotage rather than supplement their journey to graduation. His letters of recommendation, so I am told, highlighted truthfully and winningly (but without mendacious exaggeration) the strongest points of each student.

And when Ralph finally hooded the newly minted Ph.D., he remained a support for years to come—writing letters of support for research fellowships, facilitating job opportunities, and issuing invitations to return to Notre Dame for a time of to share research, pray, and reconnect at the annual Thomistic Summer Institute.

Inspired by the Cercle d’études thomistes of Jacques Maritain, these Summer Institutes gathered aspiring Ph.D. candidates, assistant professors, and many senior and distinguished professors from around the world including Lawrence Dewan, Benedict Ashley, John Haldane, Leo Elders, Tony Lisska, Stephen Brock, Kevin Flannery, and Russell Hittinger. John Hittinger, who in the absence of his brother, Ralph would call the “Designated Hittinger,” captured something of the spirit of these Summer Institutes: “We felt like a clan, a tribe of Thomists, blessed by good fortune to have such an illustrious chief in the likes of Ralph McInerny. The fight was always confident and joyful, not bitter; the weeklong meetings were both pious and rollicking.” Ralph flew us in, provided room and board, and organized an intellectual feast that benefited us—in part through these many contacts—for years to come.

Ralph’s generosity extended beyond his family, beyond his students, to the needy at large. Ralph’s kindness lightened the load of countless people—those struggling with needs of the spirit as well as those struggling with needs of the body. Michael Baxter wrote in O Rare Ralph McInerny of one such incident:

“Ralph, I was wondering if you might be willing to help the Catholic Worker, maybe get some of your friends to help too. You see, we have these bills hanging over our heads….”

“How much do you need?”

“$15,000.”

He walked over to his desk, sat down, wrote out a check, and handed it to me. I couldn’t resist looking at it: the full amount.

“Ralph, I didn’t expect you to”—but he interrupted:

“No problem. Glad to help.”

As someone raised in a family of nine children during the Great Depression, Ralph was aware of the value of money. But in his dealings with the needy, you would have thought he was an only child of Daddy Warbucks. To his struggling graduate students he passed out both his detective novels and scholarly monographs, kindly and personally inscribed, soon after they arrived at the Maritain Center. Invitations to lunch? Check. A little extra cash as needed? Check. Would you like a laptop? He had us covered.

It was fitting that he worked at a university whose mascot is the Fighting Irish. Ralph was always fighting for a good cause, even when, especially when, his team was up against it. He fought for a Catholic Notre Dame, for a just public order, and for his Church. Yet despites years of struggle, I never heard him speak with personal vindictiveness of those with whom he disagreed. Indeed, he would sometimes point out the positive in his ideological foes. In winnings battles, he was never triumphalistic; in losing battles, never despondent. In all battles, he had a confidence born of relying on One greater than himself.

When I learned the date of Ralph’s funeral, I realized that there was a conflict for me. My department has a hard and fast rule—if you miss any of the candidates’ interviews, you may not vote in a hiring decision. There was no flight from South Bend to Los Angeles that would allow me to go to the funeral and be back in time to interview one of the candidates. I hesitated about what to do. When I spoke to my colleague, Tim Shanahan, who had studied with Ralph, he asked me, “What would Ralph do?” Immediately I knew the answer. I remained at work.

The next time I visited Notre Dame, I made a visit to Cedar Grove, the resting place of Ralph’s mortal remains. I was accompanied by another of his doctoral students, Brian Kelly the Dean of Thomas Aquinas College. We prayed and reminisced. Like so many others, we miss him. Ralph spoke to me often about being here by his son Michael and his wife Connie, and here his remains now finally rest, “Home is the sailor, home from the sea and the hunter home from the hill.”