Although somewhat overshadowed by the allegory of the Cave, the myth of the ring of Gyges, and other powerful images found in Plato’s Republic, the account of the ship of fools is still memorable and compelling. While Socrates—the Athenian philosopher and mentor of Plato—is discussing with his young friends the nature of justice and the ideal political community, he finds it necessary to describe one of the perennial dilemmas of mankind—corrupt, ignorant leadership. Thus Socrates invites his listeners to imagine a seafaring vessel in dire straits:

The shipowner is bigger and stronger than everyone else on board, but he’s hard of hearing, a bit short-sighted, and his knowledge of seafaring is equally deficient. The sailors are quarreling with one another about steering the ship, each of them thinking that he should be the captain, even though he’s never learned the art of navigation, cannot point to anyone who taught it to him, or to a time when he learned it. Indeed, they claim that it isn’t teachable and are ready to cut to pieces anyone who says that it is. They’re always crowding around the shipowner, begging him and doing everything possible to get him to turn the rudder over to them. And sometimes, if they don’t succeed in persuading him, they execute the ones who do succeed or throw them overboard, and then, having stupefied their noble shipowner with drugs, wine, or in some other way, they rule the ship, using up what’s in it and sailing in the way that people like that are prone to do.

The fools “don’t understand,” continues Socrates, “that a true captain must pay attention to the seasons of the year, the sky, the stars, the winds, and all that pertains to his craft, if he’s really to be the ruler of a ship,” nor do they “believe there is any craft that would enable him to determine how he should steer the ship.”

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

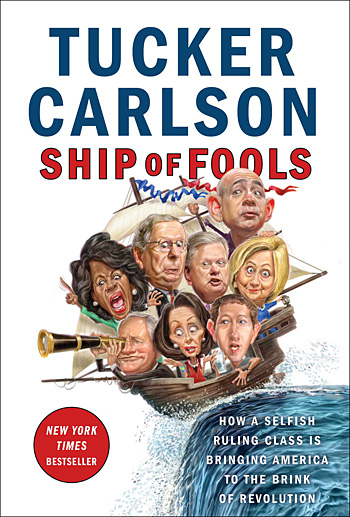

Conservative journalist, and author of Ship of Fools, Tucker Carlson sees this as an uncannily accurate metaphor for the predicament of twenty-first century America. Just as the shipowner is largely unfamiliar with nautical matters, the ordinary voter today is at best too occupied with making ends meet to familiarize himself with international and domestic politics—and at worst is far too addled by mass entertainment, propaganda, or opioids to think deeply about military alliances and federal spending. Meanwhile, like the deranged sailors, America’s coastal elites actively reject Western metaphysical and political conceptions of objective truth and human nature, and so have no chart to go by, and no guiding principle other than the naked, unbounded will of the lowest common denominator. “What was written as an allegory is starting to feel like a documentary, as generations of misrule threaten to send our country beneath the waves.” Rather than obsess about white supremacism or seek consolation in Russian hacker conspiracy theories, adds the author, both political parties should make a real effort to understand the discontent that propelled to the White House as unlikely a figure as our current president. Carlson rests his case on a point that strikes me as indisputable, regardless of how we felt about the events of 2016: “Happy countries don’t elect Donald Trump. Desperate ones do.”

While Carlson has plenty of caustic remarks for a conservative establishment which cares more about respectability and wealthy donors than it does about the well-being or opinions of the typical conservative voter, the most persistent theme of Ship of Fools is Carlson’s nostalgia for the sane and morally serious American left that has long since vanished. An entire chapter is devoted to lamenting the disappearance of a certain kind of environmentalist—i.e., the conservationist interested not in global domination but in preserving local community, saving energy, and picking up litter. As for the Democratic Party itself, the former champion of higher wages for working class families now unambiguously identifies itself as a locus of sexual experimentation and anti-American, anti-Western ideology.

While Carlson has plenty of caustic remarks for a conservative establishment which cares more about respectability and wealthy donors than it does about the well-being or opinions of the typical conservative voter, the most persistent theme of Ship of Fools is Carlson’s nostalgia for the sane and morally serious American left that has long since vanished. An entire chapter is devoted to lamenting the disappearance of a certain kind of environmentalist—i.e., the conservationist interested not in global domination but in preserving local community, saving energy, and picking up litter. As for the Democratic Party itself, the former champion of higher wages for working class families now unambiguously identifies itself as a locus of sexual experimentation and anti-American, anti-Western ideology.

Yet Carlson concludes that the fundamental problem goes deeper than the defects of any particular party or movement. Rather, it lies in the fact that the liberal democrat inevitably conducts his politics with his fingers crossed. In one especially perceptive passage, Carlson suggests that it is not the “divisive” Trump but the Beltway establishment itself which is to blame for the seething, potentially dangerous hostility bemoaned by the mass media:

Historically, rulers derive legitimacy from one of two sources: God or voters. Rulers are in charge either because they claim some higher power put them there, or because a majority of people voted for them. Both systems have been tried for centuries. Both can work. The one system that absolutely does not work and never will is ersatz democracy. If you tell people they’re in charge, but then act as if they’re not, you’ll infuriate them.

The Western jetset very often presents Democracy as if it were a messianic faith, even going so far as to overthrow governments and wage wars in its name, yet the democratic process itself is discounted whenever and wherever the people express politically-incorrect views vis-à-vis key progressivist issues, from abortion and gay “marriage” to Confederate memorials and membership in the European Union. Indeed, at times political elites seem to think the entire point of having a judiciary is so they can override and neutralize any popular referendum that doesn’t go their way. Such elites are free to loathe counter-globalist renegades like Viktor Orban of Hungary all they like, but there is surely something peculiar about having someone damned as “undemocratic” who is that rare leader that actually takes into account the majority opinion of his countrymen regarding border control.

For, as Carlson observes, with respect to immigration there is even now only one position currently permitted in American discourse:

We must celebrate the fact that a nation that was overwhelmingly European, Christian, and English-speaking fifty years ago has become a place with no ethnic majority, immense religious pluralism, and no universally shared culture or language. It’s called diversity. It’s our highest value.

In fact diversity is not a value. It’s a neutral fact, inherently neither good nor bad. Lost in the mindless celebration of change is an obvious question: why should a country with no shared language, ethnicity, religion, culture or history remain a country? Countries don’t hang together simply because.

It is worth noting here that America is far larger than most traditional countries. The state of Montana alone dwarfs Poland, and the United States covers a greater expanse than did the Roman Empire. This means that in America the cohesiveness and shared culture needed to overcome centripetal forces should be a more pressing concern than elsewhere.

Such are the issues to which real journalists call the public’s attention, even if straightforward solutions are not to be had, and so Carlson is to be commended as a gadfly who does his job. Under the influence of the decidedly elitist Greek philosopher to whom he owes his title, Carlson even invites us to examine the dogmatic assumption that democracy represents the end-all, be-all of political order:

Earlier ruling classes understood they were in charge. They admitted it and faced the consequences, including a responsibility to those beneath them. Noblesse oblige means “obligations of the nobility.” Every functioning aristocracy has taken that obligation seriously. The modern rich, by contrast, don’t acknowledge that they’re at the top of the economic heap, or even that a heap exists. They pretend they’re like everyone else, just more impressive.

Could it be that a disingenuous and unrealistic egalitarian ideology lies at the root of modern woes? Perhaps democracy itself is not a value, but just a neutral fact, neither good nor bad? Is it begging the question to fret about whether it is undemocratic to have an electoral college system, study Latin, or watch royal weddings on TV?

Whatever the case, when we assess the spiritual dimension of these matters the situation proves even worse than the dissolving country and “economic heap” described by Carlson. In addition to admitting that they enjoyed rank and privilege, the ruling classes in most societies were also wont to share—or at least acknowledge—the religion of their subjects. Today this is obviously no longer the case, and we might only be able to make sense of the hysterical tone of contemporary discourse by admitting that the divide which runs through America is essentially a religious one, and that this divide would exist regardless of whether or not the Donald were around to highlight it.

One side is animated by a vision of man as a limitless, self-creating individual entitled to go anywhere, and become anything: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life,” as the Supreme Court famously put it. What motivates the other side is a conception of man as a being both finite and fallen, a being obliged to be grateful to the particular culture and traditions which nurtured him, and called to seek his place in a cosmic order ordained by God. Put another way, the Catholic who voted for Clinton does not disagree with the Catholic who voted for Trump simply about finer points of policy, or political principles, or even particular points of the Catechism. Rather, the disagreement stems from mutually exclusive ideas about what it means to be Christian. And these mutually exclusive ideas about what it means to be Christian are bound up with mutually exclusive ideas about what it means to be human.

(Photo credit: Fox News Channel)