|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“These are my people,” I thought to myself as I listened to the panel of speakers. Or at least as much as people I had never met could be. And I never did meet any of those speakers as it turns out. It was the last day of the “Symbolic World Summit,” in Tarpon Springs, Florida, held from February 29 to March 2. One of the panelists, a poet and raconteur named Martin Shaw, gave us all homework: memorize a poem. His “assignment” confirmed me in my feeling that I was, in some sense, at home in this gathering.

The Symbolic World is the creation of Jonathan Pageau, a convert to Eastern Orthodoxy from Evangelical Protestantism as well as an icon maker turned social and cultural commentator. Pageau began producing videos on his YouTube channel in 2015. He has since formed an online community (of which your author is a member); appeared in a series with the conservative site Daily Wire on Exodus, hosted by his friend, Jordan Peterson; started a publishing house; and held two “summits” for his followers to meet in person, the one in Tarpon Springs being the second.

Pageau began his public career as an icon maker. I first heard of him in connection with the Orthodox Arts Journal, a website dedicated to Orthodox liturgy (and inspired partly by the New Liturgical Movement, a Catholic site dedicated to liturgical concerns). Pageau wrote numerous articles for the Orthodox Arts Journal on his main focus, the subject of symbolism, before becoming popular on YouTube.

Orthodox. Faithful. Free.

Sign up to get Crisis articles delivered to your inbox daily

In his videos, Pageau comments on the symbolic patterns in popular culture, such as memes—one of his first “viral” videos was about “Pepe the Frog,” something an audience member asked him about during the summit—but also in the Bible. His main contention, throughout all of his various endeavors, is that one can understand reality by grasping symbolic patterns that are not arbitrary but are inherent in the world itself and that we can discover by becoming attentive to these patterns.

Pageau is a Christian and believes the Bible to be the privileged source for understanding reality, but he also insists that one can find such patterns throughout all human cultures—so his conception of “symbolism” is a universal one. This understanding of “symbolism” has antecedents, as he readily admits, and he makes no claim to originality. But Pageau insists that understanding the world this way, which some critics might dismiss as vague or subjective, is a basic way of approaching reality that is both legitimate and necessary in a world still dominated by a rationalism that believes it can dispense with such concerns. Pageau is an important cultural figure with a growing movement, and I was eager to hear him in person.

“The Future is Symbolic”

I became intrigued by Pageau’s work in part because of my academic background. In academia, chopping up reality into small bite-sized bits is almost a job description, as evidenced by its extreme specialization. Using symbolism as a way of understanding larger patterns in history, for example, naturally appealed to me as a way of deprogramming myself from the sort of empiricism that tends to dominate in the realm of English History (which was my specialization). But in fact, I finished my first novel this past year and have started two more, so my main interest was in seeing how Pageau’s invocation of symbolism might help me in that endeavor.

The theme of the conference was “Reclaiming the Cosmic Image,” a suitably broad topic. But a more concrete theme emerged as I listened to the speakers in Tarpon Springs. The breakdown of the Enlightenment, and its reductionist and materialist views of the world, represents something like an “apocalypse” in the original meaning of the term, revealing an opportunity for traditional art and storytelling to speak to the contemporary world through grasping its symbolism.

Pageau kicked off the summit with a keynote speech titled “The Cosmos as Apocalypse.” He remarked in it that the Apocalypse as presented in the Book of Revelation represents not only the culmination of history with the coming of the Son of Man but also the reality of the world as we live it now. He meant that the image presented in that book—the “Son of Man”—provides the answer to questions of meaning that bedevil us. Are the patterns we perceive in the world mind-independent? Or are they merely a projection of our own thoughts?

Pageau asserts that Christ, the true image of Man, reveals (even for non-Christians) a connection between divinity and man, for it is only through the mediation of human consciousness that we can discern symbolic patterns in the world. Thus, Christ is the image of the End of the World, both as its final judge and its telos, and human beings live in this world “manifesting the patterns of heaven.”

If that sounds a bit vague, think of it in terms of the idea of man as a microcosm of the universe, an ancient idea that Pageau and his associates sometimes invoke. The micro (man) finds his identity in the macro (Son of Man), the Image by which all things are judged and coalesce. It follows from this that the exemplars of ultimate reality in this world are personal, not conceptual, incarnated as persons, though they can be scaled down to “things” as well. There is an “objective” world “out there,” but it is always mediated through human consciousness.

Human identity is predicated on the idea of sacrifice for Pageau. The image of Christ in Revelation is both judge and the lamb who was slain. We must sacrifice by giving ourselves up to “higher participations” while also sacrificing “down,” allowing what is lower to participate in what is higher. That hierarchical aspect of reality is very much one Pageau is keen on recovering, since so much of traditional Western civilization is predicated upon it.

As he put it, once you accept that reality is mediated through human consciousness, it becomes possible to recover “old stories” and the ancient wisdom they contain from the clutches of our contemporary civilization. Pageau made several interesting observations in his keynote speech about technology, noting that many of the same symbolic patterns prevalent in the ancient (i.e., pre-Christian) world are now running through our civilization at warp speed due to our technology, and we must subject our technology to the Son of Man to combat the dangers they present.

Some Catholics may balk at the notion of “symbolism,” especially among my “tribe” of Catholic traditionalists. Catholics who believe very earnestly in the vision of faith and reason that Catholic Scholasticism espouses might be concerned about the nature of the “symbolism” in question. They might be concerned, for example, that Pageau’s idea has something to do with the “symbolism” of Catholic Modernists in the early twentieth century, who saw the symbols of Christian faith as expressions of personal experience or preference.

Pageau’s ideas bear little resemblance to this kind of thinking and call for a return to ways of understanding that are common to many if not most civilizations. In some respects, what Pageau and company are seeking is a more holistic approach to understanding the world. Their concerns are not unlike those that motivated the Catholic professors behind the Pearson Integrated Humanities Program in the 1970s who wished to recover a “poetic wisdom” lost by modern academia. Far from encouraging people to see the world in terms of their own idiosyncratic expressions, Pageau wants people to understand patterns that would have been recognizable to both ancient Greeks and medieval Christians alike.

Other speakers at the summit spoke to variations on this theme. Fr. Stephen De Young, an Orthodox priest, gave a talk on “Friedrich Nietzsche’s Guide to the Resurrection” that tried to make the case for bodily resurrection using the thought of Nietzsche as a touchstone. Neil DeGraide, a musician, gave a talk on “Logocentric Art,” arguing that making genuine art required finding exemplars on earth of things in Heaven, appealing to the microcosm/macrocosm distinction.

Finally, Pageau shared the stage with monk and icon painter Fr. Silouan Justiniano. They discussed “The Cosmic Image in Art: Joining High and Low.” They spoke about how sacred art could be adapted to non-sacred, giving examples from their work of integrating Western artistic traditions into more traditional, iconographic art forms.

Shaw, a professional raconteur and speaker on myth provided the lion’s share of whimsy at the summit, teaching symbolism in story by telling stories. He informed the audience about the Twelve Secret Names, as well as the news that foxes smoke cigarettes. (No, I have no idea what he was talking about, but I found it delightful and suspect it may be true.)

There was much talk of recapturing traditional stories and storytelling at the Symbolic World Summit. Pageau and company mean by this that understanding symbolism can help combat, for example, the tendency of people in Hollywood to subvert traditional stories. He is thinking of things like the forthcoming Snow White movie (2025), whose star indicated the film was meant to undermine traditional ideas of womanhood.

Pageau’s press is actually producing an illustrated version of the Snow White story, and fairy tales occupy a large place in the universe of the Symbolic World (as you can guess, the work of Tolkien is popular among members). Richard Rohlin, one of Pageau’s YouTube associates, emphasized that teaching fairy tales, stories from the Bible, and the lives of the saints to one’s children was crucial to “reclaiming the cosmic image” and, presumably, retaking our public imagination back from Hollywood executives and other reprobates.

The reason for this, as Pageau noted in another of his talks, is that the culture of rational argument, evidence and counterevidence, is giving way to a culture in which such things no longer convince people, and that symbolism and story will only grow in importance in the coming years. All in all, Pageau and his associates made an eloquent case that the house which the Enlightenment built is cracking at its foundations, and the time for symbolism as a way of understanding the world is now at hand. As he put it, “the future is Symbolic.”

Symbolists and the Fear of an Internet Guru

In general, I found the speakers as impressive as Pageau in many respects. They all appeared to be genuine, serious people, and I was particularly impressed by the humility of those like De Young, who stressed that he did not have the answer to every problem the audience might have, noting in his presentation that he had changed his mind about the Resurrection and might do so again in the future.

(As an aside, I admit that attending a conference run by what sounded like right-brain artist types made me worry about how smoothly things might go. But I was impressed by how well the organizers managed the summit, something they deserve credit for.)

With regard to my fellow symbolists, all of the attendees I spoke to appeared highly enthused by the gathering as well. They numbered in the hundreds (I would guess something like 200-300 people were in attendance) and came from all over the United States and Canada (Pageau’s native country) but also from as far afield as Ukraine. All seemed eager to learn and to see their heroes in person.

There was also a decent contingent of clergy; some were obviously Orthodox, though others wore clerical collars but I could not tell what bodies they represented. Some were looking for ways to integrate Pageau’s ideas of symbolism into their work, like a chef I met from Largo, Florida. Others became interested in symbolism after being turned off by the activism they experienced at university, as was the case for one of the volunteers I met at the conference.

Another young man introduced himself to me as a filmmaker and gave me his business card. A great number of them were younger people, but I found pretty much every age group represented there. What appeared to be common to all of the people I met and listened to at the summit was a sense that the world as publicly presented by authorities in our culture did not account for their experience of it—but that Pageau’s ideas could.

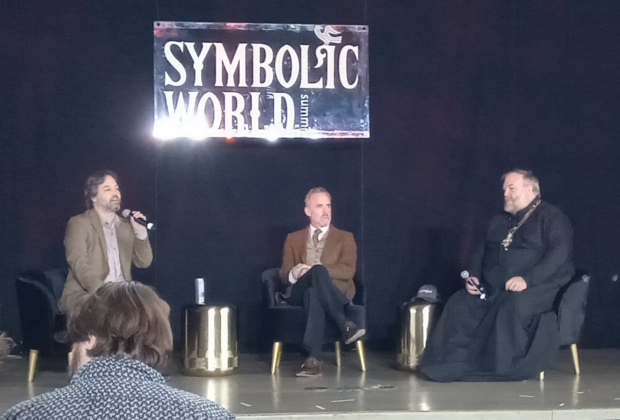

Several people I spoke to came to see Pageau after discovering him through the auspices of his colleague, Jordan Peterson. That was a theme among attendees, and they must have been pleased because Peterson turned out to be the “mystery guest” promised to attendees via email in the weeks leading up to the summit.

I admit to having hesitations about the conference and Peterson in particular, as I am by nature suspicious of cults of personality. I value my independence very much, especially intellectual independence, and I am definitely not a “joiner” by nature. Though I have come to terms with the reality that everyone needs tribes in this life, I still don’t relish many aspects of “tribal” life, so to speak. I am, as someone in college once told me, a GDI. At any gathering like this, I tend to worry about what I have gotten myself into.

As for Peterson, I admire deeply some of the public stands he has taken, but I have not read any of his books, or listened to his podcasts more than occasionally. The reason is not only my desire for independence but also because he has become something of a living symbol, and in our social-media driven world he appears at times like an amalgam of gestures prepackaged for an audience rather than a flesh and blood human being. It is all too easy to become an internet celebrity these days by bastardizing an otherwise authentic message, and this was on my mind when he first appeared on stage in Tarpon Springs.

I am happy to report that I found the reality to be much different. In person, I could tell that Peterson is a forceful, even dominant personality, but also a thoughtful one. After De Young’s talk on bodily resurrection, Peterson effectively took over the Q&A and engaged in an extended discussion with him. Peterson is in the midst of a speaking tour called “We Who Wrestle With God” and is writing a book on the subject, and perhaps he was using the opportunity to try out some of his thoughts.

Whatever the case, it might be the most illuminating exchange I have ever heard on the subject, certainly of any I have heard in person. Peterson comes across as someone who grapples with questions that real people have (“What happens after we die?”) and is able to communicate answers to the people who are asking them. Peterson comes across as someone who grapples with questions that real people have (“What happens after we die?”) and is able to communicate answers to the people who are asking them.Tweet This

To give a parallel from my own life, I had a good student in one of my classes a few years ago who approached me after class, asking about the subject of death. Bright and personable, he clearly feared the prospect of death and told me he wanted to have his mind uploaded to a computer, à la Elon Musk, before he died. I teach in a secular institution, so I could not speak of Jesus Christ and the Resurrection in a classroom to him, but the answer I did give (which I cannot recall) did little, I think, to ease his fears.

I think I would do better today, but I suspect Peterson would have given a much better response both now and then—not because he has all the answers or is more intelligent but because he embodies the life of someone who seeks answers in trust they can be found, even if they may turn out to be wrong. Peterson’s strengths are authenticity, courage, and the ability to communicate complex ideas simply enough for a wide audience to comprehend them, strengths which are more important today than novelty or originality, to my way of thinking.

The same could be said of Pageau, who also seemed like the same person he appears to be in his YouTube videos, which is no mean feat in this era of digital “reality.” Pageau is acutely aware of the problems technology poses. He even mentioned this in his concluding speech to the summit. He said that though he believes in symbolism and loves the medieval thought that exemplifies it, he is still a modern person, and making the things he teaches present in his life can be a challenge. Meeting with his internet followers is a way for him to practice what he preaches, in effect.

Catholic Reservations?

Did I find nothing to criticize at the conference? After all, what is a Ph.D. good for if you can’t passive-aggressively critique everything? I could name a few things. Peterson and Pageau engaged in a conversion on the final day of the summit on the topic of sacrifice, something to which both have devoted much thought. Peterson claimed the story of Adam and Eve means man will live in the “profane world” (his words) as sacrifice, as work. Essentially, work is the basis of civilization.

He made some interesting points about this, including the idea that everything we look at is a sacrifice because our attention could be directed somewhere else. But I wonder if his idea of sacrifice is too circumscribed; he made it sound as if every sacrifice must be a painful, bloody one, and he ignored the “unbloody sacrifices” that also contribute to civilization. I was thinking of Josef Pieper’s idea that leisure (and therefore feasting, which is also a form of sacrifice), was the basis for culture. But as there was no Q&A afterward, I was unable to pursue the point.

More seriously would I take issue with the sentiment put forth by Vesper Stamper, a novelist and artist, who made the claim that the Western world was becoming pagan again. Her assertion was met with a good deal of applause as I recall. I have written on this elsewhere and don’t want to litigate this question in an already longish essay, but I think this is a serious misreading of our current historical situation. Other than these points, however, I felt most of the presentations were very stimulating and worthy of attention.

However, readers of Crisis have probably noticed a trend among the speakers at this conference which might give them pause. Most of the participants were either Orthodox Christians or converts to Orthodoxy. The Symbolic World aims at a wide audience, and Pageau made clear his view of symbolism is not necessarily tied to any one religion. But it is undeniable that The Symbolic World is an Orthodox project, deriving, it seems to me, much of its energy from converts who have discovered a much broader and deeper tradition of Christian faith than they experienced growing up.

Is this something that should concern Catholics? The answer is no, but it probably depends on the maturity of the Catholic in question. If you are wavering in your faith, you might want to refrain. For the record, unless the good Lord has other plans, I have no urge to embrace Orthodoxy, as attractive as it can be. (And it is attractive. I had a chance to attend a Vespers service at the local Orthodox Cathedral in Tarpon Springs while at the summit, and it was marvelous. If it were only a matter of liturgy, I would certainly be tempted.)

In any case, the speakers at the conference were irenic about their faith, Pageau being the model for this. They could have leaned into this more strongly, in my opinion, and it would not have bothered me at all. The clear joy which Pageau and company obviously take in their faith is what came across to me in person, and no serious Catholic should have reservations about this aspect of Pageau’s movement.

Learning to Love the Apocalypse

So, what ultimately did I learn from the Symbolic World Summit? Well, I’m not sure how “symbolic” my next novel will be, but I feel like the experience was more than worth it. Though I will admit that seeing the world in terms of “symbolism” is going to take some getting used to, and overcoming my academic training will not be easy.

I’ve long felt my experience in graduate school and in academia altered my mind irrevocably. It may be that seeing the world in the terms Pageau sketches out will always be something of a struggle for me. A major part of that struggle is learning to see the world whole, when so many of my mental habits chop the world up into manageable bits of information.

To return to my experience at the summit, this is what I meant when I said the people I met there felt like “my people.” The experience of meeting and getting to know others who want to see the world whole was the most important thing about the summit, and I hope to continue the friendships I made there. As you may have guessed already, I suffer from a sort of invincible pride that I can somehow do everything myself, and making friends is always a good reminder of how ridiculous such pride is.

I am convinced something like the “Apocalypse” as Pageau defines it is taking place in our civilization at every level, and sharpening our spiritual sense with the whetstone of symbolism requires fellowship with those who recognize this. This is something not only I, but all serious Catholics need. And I heartily recommend the work of Jonathan Pageau and his followers to all those seeking to “reclaim the Cosmic Image” of Christ in their lives.